Dublin Core™ Application Profiles at eleven years (2011)

Note: This piece, posted to a DCMI wiki in 2011, was reformatted and lightly edited for the DCMI blog in 2019.

The notion of an "application profile" was introduced to the Dublin Core™ community by Rachel Heery at the 8th Dublin Core™ workshop of October 2000. The idea distinguished sharply between "namespace schemas" (sets of data elements as defined by their maintainers) and "application profile schemas" (sets of data elements drawn from one or more namespace schemas and optimized for local needs by implementors), introducing the notion of "mixing-and-matching Dublin Core™ elements with elements from related vocabularies.

By design, an application profile was limited to using elements defined elsewhere: "If an implementor wishes to create ‘new’ elements that do not exist elsewhere then (under this model) they must create their own namespace schema, and take responsibility for ‘declaring’ and maintaining that schema" Heery and Patel 2000. The role of a application profile was to document how elements were constrained, encoded, or interpreted for application-specific purposes in order to promote the harmonization of metadata practice within broader communities, though it was anticipated that machine-processable expressions of profiles "based on data models such as RDF" might allow metadata interoperability to be automated Usage Board 2003. The application profile was envisioned as a machine-understandable, narrative response to the question, "What terms does your metadata use?" Baker et al 2002.

Towards formalized application profiles

The initially very general conceptualization of application profiles was interpreted in many incompatible ways. Making application profiles comparable among themselves would require a shared modeling basis, and the obvious candidate for that model was RDF. First steps towards formalizing the notion of Dublin Core™ application profiles on the basis of RDF were taken between 2000 and 2003 in the context of the EU Schemas Project and in the CEN/ISSS Workshop on Metadata for Multimedia Information--Dublin Core™ (WS/MMI-DC) of the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) CEN 2003.

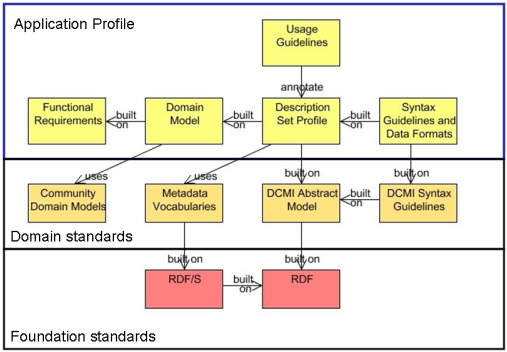

Work began in 2003 on a DCMI Abstract Model (DCAM), which was intended in part to provide a more solid modeling basis for application profiles. The formalized notion of a Description Set, centerpiece of the DCAM, provided the basis for formalizing the notion of a Description Set Profile (DSP) - the expression of structural constraints on a Description Set in the form of "templates" for its components (Descriptions and Statements). The Description Set Profile, in turn, formed the centerpiece of the Singapore Framework for Dublin Core™ Application Profiles, which defined application profiles as a set of specifications documenting, however simply, the design process by which Functional Requirements informed a Domain Model of entities to described by the metadata, as the basis for a Description Set Profile detailing vocabularies used and what constraints, in turn providing the basis for concrete metadata formats.

An Application Profile, under this model, was seen not just as a schema, but as a packet of specifications and Usage Guidelines documenting an application-specific metadata model -- a model in turn grounded on domain standards such as Community Domain Models, Metadata Vocabularies, and the DCAM with its related syntax guidelines. Domain standards were themselves grounded in the "foundation standards" of RDF. A primer for creating application profiles on this basis, Guidelines for Dublin Core™ Application Profiles, was published in 2009, and the DCMI Usage Board developed and tested criteria for evaluating the conformance of application profiles according to the guidelines and principles articulated in the Singapore Framework.

The Singapore Framework approach to application profiles was intended to guide the design of RDF-compatible instance metadata -- records based on application-specific formats, using RDF vocabularies, templated according to the Description Set Profile constraint language, and expressed in concrete syntaxes with a defined relationship to DCAM (such as HTML, XML, and RDF/XML). DCAM's basis in RDF would ensure that the contents of DCAM-based instance metadata would be straightforwardly expressible as RDF triples and thus as Linked Data.

More fundamentally, the Singapore Framework approach to application profiles was intended to bridge the gap between traditional data-management approaches, grounded in metadata records with defined document structures, and new Semantic Web approaches, based on the notion of a theoretically boundless data graph.

In order to do this, the authors of DCAM defined constructs not provided by RDF itself - specifically, the notion of a bounded Description Set (roughly analogous to the RDF notion, ambiguously defined at the time, of a Named Graph). DCAM also constrained the infinite possibilities of an RDF graph to a specific set of patterns intended to capture the Dublin Core™ community's "style" of metadata, with its particular use of URIs, text labels, Syntax Encoding Schemes (datatypes), and Vocabulary Encoding Schemes.

In the text Interoperability Levels for Dublin Core™ Metadata of 2008, shared application profiles were seen as the highest level of interoperability in a four-tiered hierarchy ranging from the human but non-machine-actionable interoperability of shared natural-language definitions, to interoperability on the basis of formal semantics (RDF), and culminating in interoperability based on shared natural-language definitions, formal semantics, and a shared model of a metadata records using the same terms with the same constraints.

The future of Dublin Core™ application profiles (as seen in 2011)

Starting in 1999 with IETF RFC 2731, a set of simple guidelines for embedding metadata in a Web page, DCMI embarked on the development of more sophisticated models and syntax guidelines in response to demands from the Dublin Core™ community. DCMI had published a vocabulary, people wanted to deploy that vocabulary in applications, and there was a serious lack of implementation guidance, so people looked to DCMI to fill the gap.

Ten years later, the technological landscape was significantly different. The idea of Linked Data, introduced as a more accessible and focused variant of the Semantic Web vision, had acquired significant momentum -- a trend which validated DCAM's focus on RDF-grounded metadata, but which also overshadowed DCAM and its DCMI-specific terminology with standards and tools developed as part of the mainstream Semantic Web technology stack. Notable examples include the development by W3C of RDFa, a solidly tested and deployed specification for embedding RDF metadata into normal Web pages, providing an alternative to the DCAM-based DC-HTML guidelines. The notion of a SKOS Concept Scheme in W3C's Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS), providing a widely understood near-equivalent to the DCMI-specific notion of a Vocabulary Encoding Scheme. A renewed effort to clarify the semantics of Named Graphs promises to provide an RDF construct analogous to the Description Set.

The DCAM-based approach to application profiles, for its part, was not widely implemented, though it was widely cited and served as a source of inspiration to metadata designers in its broad outline, if not in its details. Notable exceptions included the Dublin Core™ Collections Application Profile and the Eprints Application Profile, also known as the Scholarly Works Application Profile (SWAP).

A DCMI Usage Board review of SWAP in 2009 uncovered weaknesses in the DCAM-based specifications while suggesting that DCAM-based approach had become overly cumbersome for metadata designers because of the lack of tool support - both for translating an application profile into working formats and for authoring an application profile as a document - and overly cumbersome for application profile reviewers due to the tedium of checking detailed constraints by hand.

In 2010, DCMI undertook a critical review of the DCAM specification stack as the basis for a discussion at a joint meeting of the DCMI Architecture Forum and the W3C Library Linked Data Incubator Group. Discussion at the meeting revealed a lack of consensus about the meaning and value of the DCMI Abstract Model and related specifications. While some discussants took DCAM in the sense intended by its authors - as the specification of an abstract syntax for metadata records rooted in RDF - others saw it as a "meta-model" describing the components of metadata descriptions at a level of abstraction independent of any basis in RDF.

It is clear that its authors intended the DCAM as the basis for automating the creation and validation of metadata records, the contents of which can straightforwardly be exposed as RDF triples. Attaining such degrees of interoperability and automation implies the use of a well-defined metadata model, and the authors of DCAM shared the view that RDF currently represented the only candidate model with any traction. Proponents of the "DCAM as meta-model" view, in contrast, feel that the model has value independently of RDF - i.e., that the notion of "statements" grouped into "descriptions" and enclosed within a "description set" are valid in the absence of RDF's grammar of properties, classes, datatypes, and statements. Whatever the merits of these two quite different views of DCAM, it was also clear that the specifications had been written defining DCAM as a basis for specifying RDF-compatible metadata records, and that if DCAM were to be defined as a meta-model independently of RDF, the base specifications would need to be extensively re-written.

As of 2011, the function and value of DCAM remain unclear. In the absence of a strong community of implementors, the DCAM remains a largely theoretical specification, and its authors have moved on to other projects. Regaining momentum on DCAM as a basis for specifying RDF-compatible metadata records would require more resources -- authors, editors, and implementors with clear requirements -- than DCMI, as a lightly-funded vocabulary maintenance organization and metadata community platform, can bring to bear. On the other hand, the project of re-casting the DCAM as a meta-model would require equally as much effort, together with a well-founded story for its function and value in the metadata landscape. Practically speaking, DCMI has little choice but to leave the specifications in place, both for their value as historical contributions and potentially as sources of requirements for other projects, with status clarifications as offered here.

The DCAM-based approach to application profiles as outlined in the Singapore Framework was an attempt to automate the cycle of development from functional requirements through the development of a domain model, the description of entities in that domain model following defined constraints, and the generation of metadata record formats on their basis - compatibly with RDF.

However, meeting this challenge remains a problem for research. Over the years, alternative approaches to "structural constraints" and "validation" have been explored within the Dublin Core™ and Semantic Web communities. In 2007, Alistair Miles proposed "Son of Dublin Core™", an approach for encoding and validating "graph-based metadata" using a concrete XML syntax together with language for expressing application-specific syntax constraints over a metadata graph.

In the name of validating the quality of RDF triples, proposals have been put forward such as Clark & Parsia's "integrity constraint validator", Pellet, which treats OWL "as a schema or validation language for RDF data via auto-generated SPARQL queries that can be executed on any SPARQL-enabled RDF store" by interpreting OWL ontologies with closed-world assumptions in order to detect constraint violations.

Dan Brickley has proposed a more pluralistic and eclectic approach to application profiles encompassing a wide range of human-readable and machine-processable methods for documenting metadata patterns, from simple lists of namespaces used to Web documents, metadata exemplars, and example queries.

DCMI recognizes that validation and quality control of data exposed as Linked Data remains crucial as a problem, perhaps now more than ever, but acknowledges that this problem can only be addressed by organizations or projects capable of sustaining a push to their resolution.